Introduction

GSAR in British Columbia

Volunteer ground and inland water search and rescue in British Columbia has evolved immensely since the 1960/70s, with the shift away from Civil Emergency response to finding lost persons, and rescuing those injured or stranded. Many of the GSAR groups in BC were formed following a high-profile incident in their respective communities, or through volunteers recognizing the need for better organized search capability and/or specialized rescue techniques, equipment and training.

Evolution of GSAR response

Early GSAR responses were ad hoc and generally disorganized. The unpaid volunteers did the best they could with what little equipment and training they had. As governments and agencies realized the need for a more appropriate level of response they gradually began to offer more support to these volunteer groups, recognizing that unpaid volunteers with local knowledge still provided the most cost-effective solution.

Even once supported, equipped and trained, the overall incident response approach was not always consistent. It took large-scale incidents and subsequent SAR reviews to improve the level of professionalism required in a SAR incident response. The last two decades have seen even more significant improvements in the way SAR volunteers organize and implement the typical SAR response. Not only are they better prepared through planning, training and equipment, but they are also more aware of the ‘big picture’ and recognize the need to manage the response from the outset. Part of this professionalism is ensuring that SAR volunteers are afforded the same protection and rights concerning their health and safety as paid agency staff.

SAR volunteer health and safety

The British Columbia Emergency Response Management System (BCERMS), the Incident Command System structure under which all emergency response in the provinces operates, has the following objectives:

- provide for the safety and health of all responders

- save lives

- reduce suffering

- protect public health

- protect government infrastructure

- protect property

- protect the environment

- reduce economic and social losses

To fulfill the number one objective of BCERMS, Emergency Management British Columbia (EMBC) develops policies under which SAR volunteers operate, including The Public Safely Volunteer Lifeline Safety Policy. The Search and Rescue Safety Program Guide and Provincial Operating Guidelines (initially published in 2009) provide additional direction and guidance specific to Search and Rescue related issues. All these documents are available at http://www.embc.gov.bc.ca . They should be a fundamental part of any risk assessment and management strategy and will provide a formal reference point for any critical decision-making. EMBC and the British Columbia Search and Rescue Association (BCSARA) co-chair the SAR Volunteer Joint Health and Safety Committee, which can be reached at ohs@bcsara.com for any health and safety questions or concerns.

Coverage

SAR volunteers are provided with injury, disability, and accidental death coverage under an agreement between the Federal Government and the Province of British Columbia under a task number. This coverage is administered by WorkSafe BC or in some cases under an insurance policy provided by the Province. While SAR volunteers are not considered ‘Workers’ under the Worker Compensation Act, the coverage provided is the same as for Workers.

The requirements pertaining to Health and Safety for Workers within WorkSafe BC regulations are not applicable to SAR volunteers. The primary references for SAR volunteers are the Public Safety Volunteer Lifeline Safety Policy, the SAR Volunteer Safety Program Guide, Provincial Operating Guidelines, and other Operating Guidelines established by SAR Groups specific to their operation and hazards.

Risk management/mitigation

Everything we do has an element of risk; driving to work, taking a flight, crossing the road etc. However, most if not all everyday risks have been mitigated to some extent to make them manageable. Often the need to mitigate risk is initiated by an event that caused injury or even death. Many formal SAR reviews have had a positive impact on SAR volunteer safety in helping to improve training and establish policy and/or protocols where required.

All responses to SAR incidents are different in some form or another, be it in location, environment and/or severity; the variables are infinite. A straightforward ground search in a rural area may at first appear as a low-risk endeavour, but multiple hazards can compound to present significant risks. Such risks are not always apparent at the outset and consequently any risk assessment/management strategy must always be dynamic and respond appropriately.

Two distinct approaches are currently in place regarding hazard assessment and risk management: rule-based policies and judgement-based protocols. EMBC has developed specific policies that can be considered ‘rule-based’ (i.e. the avalanche response policy). Such policies clearly demonstrate a ‘Go/No-Go’ approach and are appropriate in such a high-risk environment. However, there are countless situations where a ‘rule-based’ approach would not be applicable and would likely cause many SAR responses to be halted. The onus is therefore on all SAR volunteers to continuously assess their exposure to hazards and manage risk whenever and wherever feasible.

There are many factors that ultimately affect the degree of risk management/mitigation required. Some are obvious; some are not. This tool attempts to identify an extensive list of factors in an effort to ensure that they are considered when making decisions that could result in serious injury or even death.

This should not be interpreted as a ‘Go/No-Go’ gauge, but rather as an objective method to identify hazards and reduce risk.

Approach to response assessment and decision making support

The card and reference guide are designed to be used by SAR Managers in the context of the overall response, and by Team Leaders specific to their team assignment. All SAR volunteers should be aware of these tools as part of the safety program.

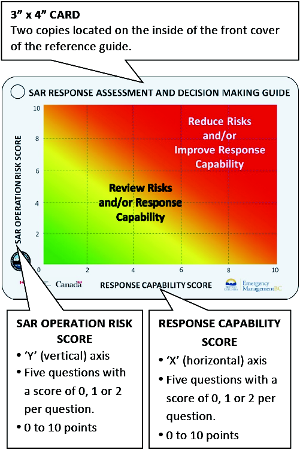

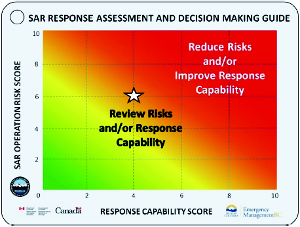

The approach taken in developing this tool was to evaluate two sets of criteria in a dual-axis heat-map card format. The simple ‘green is safe’, ‘yellow is caution’ and ‘red is danger’ convention is easily recognized and understood. Once that format was established, a series of questions was required along with a scoring system.

The following generic elements and questions were developed to generate the values required for the ‘X’ and ‘Y’ axis totals:

SAR operation risk score (‘Y’ Axis)

- Operational complexity

How complex & complicated is the task? - Activity hazards

How high are the hazards in the activity? - Environmental conditions

How high are the environmental hazards? - Vulnerability

How exposed and vulnerable are the team members? - External influence

What is the level of pressure due to survivability, media, family and/or other?

This element was the most difficult one to define. Subject ‘survivability’ should not result in risks being ignored. However, the combination of urgency along with family, media and/or agency pressure (to resolve) creates an atmosphere of stress that often leads to undue risks being taken

Response capability score (‘X’ Axis)

- Personnel training

What level of training do personnel have? - Personnel experience

What level of experience do personnel have? - Personnel mental & physical preparedness

How mentally & physically prepared are personnel? - Planning

How much planning has there been? - Resources

What is the level of resources available?

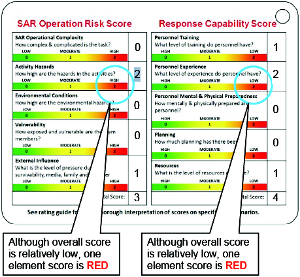

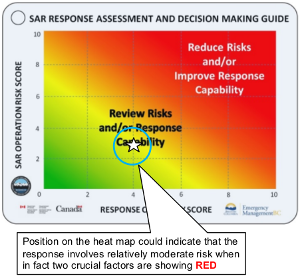

Understanding the scoring

When arriving at two total scores, the corresponding location on the heat map on the front of the card may indicate an area of low to moderate risk (green or yellow). However, one or more individual elements on either axis may have a high score (2). It is therefore important to not just look at the overall rating, but to also consider how to mitigate and manage individual critical elements. This in turn will lower the overall score.

Using the rating guides

The rating guides are intended to provide examples of how to score the ten factors as they relate to several SAR disciplines (ground search, rope rescue etc.). The intent is to provide a degree of consistency in how the user interprets the scenario. ‘Ground Search’ will no doubt be the most widely used and is therefore most easily viewed as the default rating guide. Once the user has had some experience using the tool, the ability to score a scenario should become second nature.

As mentioned earlier, most GSAR responses are dynamic events and what may commence as a ‘ground search’, may become a ‘rope rescue’. At this point the circumstances will likely require a re-evaluation of the situation and call for a review of the scoring using the ‘rope rescue’ rating guide.

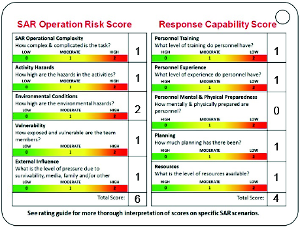

Example

A lone skier has become separated from his party on the return leg of a day trip. It is now late afternoon and the weather forecast calls for heavy snow. Temperatures are expected to fall to -10C with strong winds. The subject is experienced, but has minimal equipment for surviving any length of time in severe weather. Location is Zoa Peak area, Coquihalla summit (8,000’). Slopes are moderate, but there is potential avalanche risk. First SAR group on call has immediately summoned mutual assistance from four other SAR groups. MOT avalanche techs (2) are on site and are part of response. All SAR personnel are in good to excellent physical condition and all field personnel have some degree of training and experience for the conditions. Communications are patchy. Command is in place and well-equipped to manage the incident. Pre-plan is in place. Little interest from media. Friends, but no family are on scene.

Pre-planning

Pre-plans are an essential component of a safe, efficient and effective SAR response strategy. They can range from simple/generic to complex/detailed:

- Generic disciplined-based scenarios (ground search, rope rescue, swiftwater rescue, avalanche etc.)

- Generic disciplined-based scenarios in specific areas, complete with travel times and geographic information

- Specific scenarios (often multi-disciplined) in specific locations

- Specific scenarios (often multi-disciplined) in specific locations, complete with pre-planned assignments, staging area, mutual assistance, time/distance stats etc.

Pre-plans can be based on specific hazards that have not had a history of incidents, but pose a high risk to anyone venturing into them. Although some SAR groups have extremely large areas to deal with, there are often specific locations that see multiple incident responses over time. These are good examples of where a detailed pre-plan would be effective. Higher call volume SAR groups will likely have multiple locations that see similar incidents occurring, often within short time periods. A good example of an appropriate complex/detailed pre-plan would be a community evacuation in response to a disaster scenario, such as an interface fire or flood.

Resource lists

Current, accurate resource lists will greatly assist in expediting resources in an efficient manner. Having this information readily at hand during initial deployment will ensure that the appropriate resources are activated in a timely manner. Human resources can be linked to pre-plans and should address deficiencies that the home SAR group is unable to develop in-house.

Equipment may belong to other SAR groups, but may also be available at short notice from other agencies or even recreational groups in the case of ATV’s and/or snowmobiles.

Mutual assistance

Along with resource lists, having a good working relationship with other SAR groups and agencies will ensure that an appropriate level of response can be activated at any given time. This is particularly important during weekday/workday hours when SAR volunteer availability is generally low.

Rating guides

Notes:

- The following factors are provided for guidance only and may not cover all aspects of a specific SAR response

- Factors shown under some elements are consistent throughout

- In the LOW category, under the element ‘Personnel mental & physical preparedness’ is the phrase “Personnel are negative and question decisions”. This is in no way intended to imply that SAR volunteers should not express concerns regarding their safety