Think of any movie you’ve ever watched that has a Search and Rescue component in it. For example, let’s look at the recent movie San Andreas where Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson plays a SAR helicopter pilot / superhero. How are we (SAR responders) represented?

In the opening scenes of the movie we’re introduced to Ray (played by The Rock) who is inexplicably a helicopter pilot, a medic, and a technical rescue specialist. Not 10 minutes in, he’s risking his life, that of his crew and the “ride along” reporter and camera person. He flies the chopper, performs an impossible maneuver, then turns over piloting duties to his copilot while he is lowered to the subject, rips the car door off with his bare hands, and rescues the female occupant.

Now I’m not saying anyone actually believes Search and Rescue members can do any of this, but the depictions of how SAR people behave in the media have a subtle effect on how the public perceive us in reality. Media reports often depict SAR volunteers “risking their lives” to get to the subject, and depict us as undertaking incredibly difficult tasks as part of our jobs. These are misconceptions that have a distorting effect on how the public thinks of SAR.

The CSI Effect

Yeahhhhhhhhhh! We don’t get fooled again! This is the music that’s going through my head on EVERY task.

There’s a term for how the depictions in the media change how the public perceives a career or role. It’s commonly known as the “CSI Effect”.

The effect is named after the original show CSI: Crime Scene Investigation which premiered in the year 2000 (coincidentally the year I started volunteering for SAR). The show follows a team of forensic scientists in their role as crime scene investigators as they assist the police to solve crimes. In typical fashion, the actual work of an investigator or scientist which usually takes months or years is compressed into a 45 minute time slot, and is amped up beyond all belief to depict a flashy, stylish and exciting job.

The CSI Effect itself refers to what law enforcement officers, lawyers, judges and other legal professionals noticed while charging, prosecuting and attending trials; that the public believed that many of the tools and techniques represented on the show were real. They expected to be presented with detailed forensic evidence for even the most minor of offences, and that facial recognition and fingerprint analysis would be conclusive. Of course the reality is that none of the forensic science is as conclusive as is depicted on TV, and that trials are full of conflicting accounts as people’s memories faded. The effect of the show was so pervasive that both prosecutors and defence lawyers had to spend more time in court teaching the juries what was real, and what was possible, to counteract the perception the public had built up.

The effect is also responsible for a surge in interest in a career as a forensic scientist, so it’s not all bad.

How could a warped perception of Search and Rescue make our jobs harder?

Response time

People talk about Search and Rescue as “first responders” and we’re sometimes called the “fourth emergency service” after Police, Fire and Ambulance. While it’s true that we’re first responders, placing us in that group of three forces people to associate us with a level of response that we just cannot deliver. In movies and reality TV shows, Search and Rescue people respond in minutes, running “Code 3”, with lights and sirens, speeding through traffic, showing responders running as fast as they can. Nothing could be further from the truth.

A typical member of the public knows that they can call 911 and within a few minutes have the police, fire or ambulance responders at their door. Similarly, when someone is lost in the bush, they believe that a SAR team should be responding within a few minutes to rescue them. We’re sorry to say this is not the case.

Even if SAR members ran from their houses and were allowed to drive their personal vehicles “code 3”, and even if the helicopter pilots (who also have lives outside of their jobs) were standing by waiting for a call, the nature of the wilderness in British Columbia means that it can he hours before we locate you and have a rescuer on scene. The fastest I have ever witnessed a SAR team respond was 45 minutes, and that’s because we were doing a training exercise with our helicopter provider, and were minutes from the subject.

The reality is that SAR members can take from 45 minutes to an hour to leave their work and homes, and to drive to the muster site for a rescue. Only when our management team has enough SAR members on scene can even the search phase of the operation commence. It can take 30 to 90 minutes to locate someone and rescue them from this point, assuming that they’ve left a trip plan, have a working smart phone or satellite locator device (see below).

In many ways, we are our own worst enemies in this respect – we’ve been delivering a very high level of service for so long that the public perception of how fast we can respond is coloured by the glowing media reports of how professional and consistently excellent our service is.

Communication and Smart Phones

Another pervasive misconception about SAR revolves around the expectation that many hikers have that their phones will work in the backcountry. They believe SAR members can “ping” their phone to get their location, that the battery in a smart phone can last all day and still have enough energy to call for help. We’re sorry to tell you that you’re wrong.

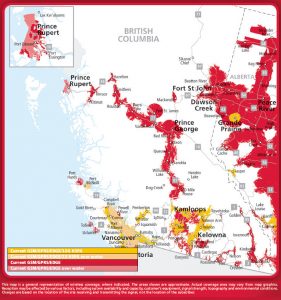

Smart Phones are amazing devices, but therein lies the flaw. They can make phone calls, be used as a navigation device, and dozens of other things, with specialized apps for weather and avalanche conditions. The issue is that most of BC doesn’t get any cellular signal – as you can see from the map to the right. Cell signal in BC largely follows the highways through the valley bottoms, and very quickly disappears on the edge of urban areas. Even within the lower mainland of BC, the cellular signal is not present in many parks, and is likely to be intermittent during a hike.

The misconception about smart phones is whether SAR can “ping” the phone. Film and TV shows (including all of the various CSI franchises), without exception, depict an almost magical ability for anyone, including hackers, to track someone using their cell phone. To an extent, this ability does exist – I am the author of an application to assist SAR teams to locate hikers – but it is nowhere near as simple or as accurate as it seems on TV. We do have ways to gather your location but it requires a phone with a good signal to multiple towers, and cellular data. Needless to say, it doesn’t work at all if the batteries are dead.

The truth is that your phone can be very difficult to locate unless you have set up some pre-configured way to share the location (like with a friend) and neither the police nor Search and Rescue are going to have the time to configure your particular app while you’re on the other end of a call to a 911 operator. Also, most of our province doesn’t have any cell signal outside of urban areas!

Location devices

Satellite Emergency Location Devices (SEND) such as InReach and Spot, or Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) have become common and affordable. But similar to my comments on response times above, the public perception is that triggering such a device will result in SAR being on scene within minutes to assist. Again, the reality is quite different. In a popular post on my personal blog I recounted an experience our SAR team had with a PLB response – and how a combination of weather and terrain delayed rescuers by over 12 hours.

Locations devices also have their faults, and are not fool proof. In another post on my personal blog I recount how a malfunctioning SEND device caused our team to respond to a fisherman who was very surprised to see us. His device had been activated in his pack. Like most technology, using these devices takes training, experience and some careful handling.

Putting ourselves in Danger

The final thing I wanted to talk about is the pervasive myth that SAR members “put their lives in danger” when responding. There is a certain amount of truth to this, but only a little. Responding to a search will always have more risk than, for instance, staying at home and watching TV. Just driving to the search entails risk – of an accident in traffic. And certainly hiking at night, in steep terrain and bad weather is an injury prone environment.

The fact is, if we are doing our jobs right, we’re managing those risks. The unofficial motto of SAR is “Safety of self, team and subject” – and the order of that statement is important. If you or your team are taking unnecessary risks, you’re a liability to the entire team. Most of our training involves safety procedures, risk assessments, and managing risk. We’re wearing the right personal protective equipment, we have the appropriate training and procedures, and we have a support network of other SAR members. Most of my work as a SAR manager is ensuring we have the resources to respond and rescue our own members if one of them is injured. In my 18 years in SAR I’ve only attended one search where there was a major injury.

Summary

In this article I’ve only covered some of what I feel are the most harmful TV “Tropes” related to SAR. The most damaging effect? How we are depicted may lead the public to expect rescue in a shorter time, to more remote locations, and under conditions we can’t meet. As a result, there’s a possibility that the public may feel they’re safer than they are, or that they don’t need to prepare as much as they should.

On a humorous note, feel free to continue believing that each and every one of us is capable of flying a helicopter, patching up a gravely wounded subject, and that we can rip doors off cars, move rocks with our minds, or speak to animals. As long as you’re prepared for your wilderness activity, and aren’t too disappointed that we all don’t look like The Rock.

Author

Michael Coyle has been a SAR volunteer with Coquitlam Search and Rescue for 18 years, and is an active member of the BC Search and Rescue Association, serving on the Media Committee and Technology Committee. He blogs about the intersection of SAR and technology as Oplopanax Horridus, and is the author of TrueNorth Geospatial, a mapping application designed for Search and Rescue and other Backcountry professionals